Chapter 5 The Arrival of the French

5.3 Pierre Milius:

Survey of Mr Bass's Western Port.

Port Jackson, 18th November 1802

What a dreadful time I have had since my ship, the Naturaliste, under the command of Captain Hamelin, arrived here at Port Jackson on 24th April.

I have been in poor health ever since leaving the island of Timor some months ago. This was probably brought about by poor and insufficient food, bad water, bad wine, bad weather-bad everything!

The best time I have had as Second in Command of the Naturaliste was when for one week, with myself in command of two ship's boats and crews, we explored Western Port.

This is the fourth time I am standing on rocks at South Head, Port Jackson, waving goodbye or welcoming my shipmates from the expedition.

We had lost contact with the Géographe and Commander Baudin. However, we had on board some of the 20 copies of a map by Matthew Flinders of Bass's Strait and Van Diemen's Land. My Captain, knowing the suggested timetable for exploration, decided to continue with his orders in resurveying and making corrections to the charts if errors were found in parts of Van Diemen's Land and Islands, as well as Wilson's Promontory and Western Port, then sail for Port Jackson.

On our arrival at Port Jackson on 24th April, the English made us very welcome even though we could still be at war with them. The Governor, Captain King, even sailed over to our ship in a vessel called the Lady Nelson, to inspect our Passport and welcome us.

Our sick-myself included-were taken ashore to be hospitalised. The English even helped with ship repairs and supplies of food.

Captain Flinders arrived at Port Jackson on 9th May and told everyone of his meeting with the Géographe and Commander Baudin at Encounter Bay, and that Commander Baudin intended to sail to Port Jackson.

After some time at Sydney Captain Hamelin, on the Naturaliste, concluded the Géographe was ‘lost at sea' and decided to keep to the timetable and sail to Isle de France on 18th May.

The Commander left me, with several other sick crew members, behind because we were too sick to sail. Then, on 20th June, the Géographe appeared off Port Jackson heads. The ship was so dilapidated and the active crew were so few, because of the number of sick, that it could not sail into the Port. Governor King sent a boat to tow the Géographe into port. Our joy was overwhelming at seeing our ‘lost' shipmates.

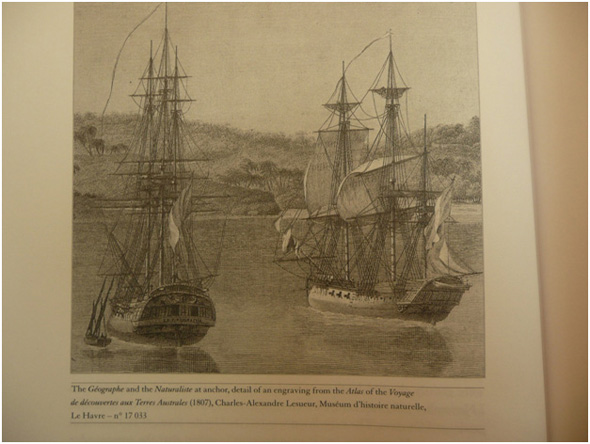

The French ships Géographe and Naturaliste, from the Baudin expedition. SLV

On 28th June the Naturaliste sailed back into Port Jackson, due to impossibly bad weather conditions they met in the south.

On 18th November, the Géographe, the Naturaliste and a small cutter, the Casuarina, which was purchased from the Governor, left for Isle de France without me. The Casuarina was commanded by Louis Freycinet, second in command was Leon Brevedent.

Arrangements had been made for me to sail, as soon as I had recovered, on the next available ship going to China. I would then make my way independently to Isle de France. What a task! A truce had been declared between France and England, but how many ships would be sailing into that port, and how often?

I have had more time these last few weeks to reflect, document and help others with records of our time in Western Port. In particular Monsieur Péron, the zoologist/naturalist aboard the Géographe.

He hates Commander Baudin and holds him responsible for all the expedition's misfortunes. I know he has made friends with several leading merchants in the colony, and also Lieutenant Governor William Paterson, whose garden cultivation, layout and planning he admires so much. I think Mr Péron is also acting as a spy for our Government.

My favourite Englishman is Dr George Bass. I was able to have several conversations with him. We shared many anecdotes. I was able good humouredly to point out his mapping inaccuracies-which Governor King had unfortunately instructed Matthew Flinders to incorporate in his overall maps of Bass's Strait and its islands. Mr Bass in turn pointed out that we, the French, had the advantage of his previous mapping attempts from a small whaleboat, and that frankly most of his efforts went into surviving the rigours and hardships of the journey. Any way, he said I was not good enough to receive from the Governor a small cigar case made from the keel of his whaleboat. Only Commander Baudin was good enough for that gift. Governor King would present it.

I remember Western Port in the following way, which I have described to M Péron:

We spent a week on this last work, and found that the English chart was very incomplete. We found, for example: that the sort of large peninsula marked on Mr Flinders' chart as occupying the head of the Port is really an island, which Midshipman Brevedent was the first to circumnavigate and which we have named French Island; that Western Port has two entrances-the eastern one, impracticable for big ships, and a western one, itself divided into two separate passages by a considerable shoal in the middle of the channel; that this harbour offers good anchorage everywhere and is sufficiently vast to hold a prodigious number of ships of all sizes; that landing there is easy; that the terrain is formed essentially of a reddish, medium-grained soil, backed by layers of sandstone; that in various places there are fresh water streams capable of supplying visitors' needs; that the soil is fertile and the vegetation very healthy; and that the country is well timbered-that, in a word Western Port is one of the handsomest harbours that one could possibly find and that it possesses all the advantages that may, one day, make it a valuable establishment.

The height of the tides there is ordinarily about two metres, but it appears that they can, in certain circumstances, rise to as much as five metres.

During our stay in Western Port, we had a meeting with the natives of this part of New South Wales. The human species did not seem to be numerous; the natives we were able to see appeared suspicious, defiant and treacherous. Their language seems to have nothing on common with the inhabitants of Van Diemen's Land, apart from the excessive rapidity of its pronunciation. Furthermore, the people differ markedly from those of D'Entrecasteaux Channel in all their facial features, the shape of their head and their sleek, very long hair. They have fine, regular teeth, and it appears that they do not have the custom of pulling out any of the front ones.

These people's food consists particularly of shellfish. They paint their body and face with red and white stripes, crosses and circles and pierce the septum of their nose so to put in a stick. They wear a necklace of coarse straw, and also like the natives in Van Diemen's land blacken their body and face with crushed charcoal. Of the thirteen individuals visible, only one was covered by a sort of cloak of black animal skin; all the others were absolutely naked. To warm themselves, or through lack of concern, they light the most disastrous blazes in the woods. There can be no doubt that these populations belong to the same race.

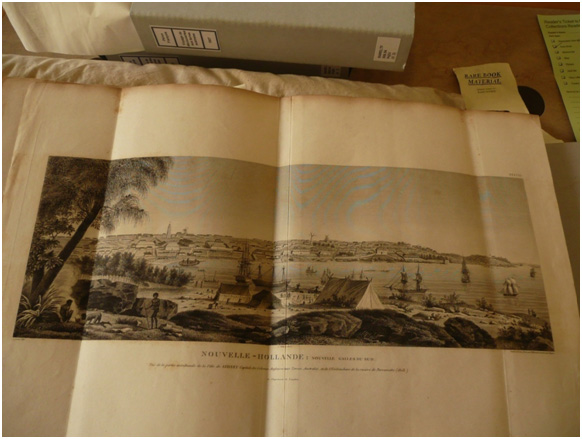

Sydney Town, looking from Bennelong Point. The French encampment is alongside that of Matthew Flinders. SLV.

Previous Chapter | Chapter Selection | Next Chapter | Download Chapter