Chapter 3 Further Exploration Essential

3.1 Ensign Barrallier::

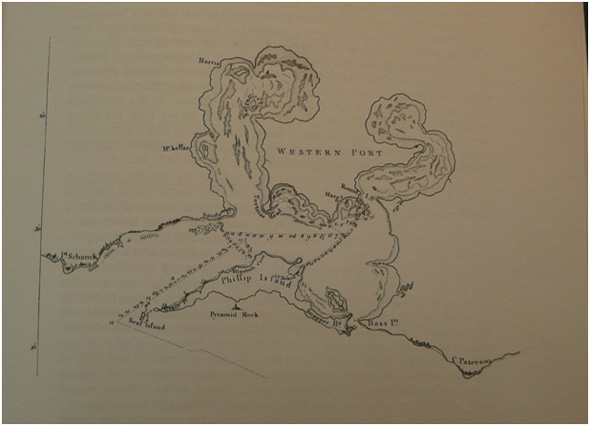

My survey work and exploration of Western Port.

22nd April 1801

I must write to my Father and Mr Greville when I get back to Sydney; so much has happened.

Captain Grant is making urgent preparations to leave the port. Fortunately the Captain, Mr Murray and Mr Bowen and myself have just about completed surveying and all the exploring that we had originally decided to carry out. Mr Caley, our botanist as usual is very uncommunicative, but we have all shared with him some of the samples that we have collected. He will report his findings to the Governor and Mr Joseph Banks in England.

I have had a wonderfully exhilarating adventure. The sense of freedom from any constraints. The freedom to do things and be totally responsible for my actions, as long as they fit into our Captain's plans. Exploring all the land around the port, surveying and charting, shooting for collections, shooting for the dinner. I think I am the best shot in our party. We have seen signs of the local Indians, including finding a canoe that is very different in construction to Indian canoes at Sydney. The two Indians we have with us cannot, or do not wish to make contact with any local Indians.

The next task we face when we leave the port on our return journey, is to survey and chart the approximately 70 miles of coastline, from the port to Wilson's promontory. We are to establish its exact latitude and longitude.

During quiet times Captain Grant sometimes shared his private thoughts with me. This actually started in Sydney when I was assigned with a marine to accompany Captain Grant, his First Lieutenant and some sailors to find one of his ship's boats that was originally lent to a person. The person was then overcome by convicts who stole the boat. We were not able to recover the boat but we did have several days of adventure and hardship.

Here at the port, when we camped out several times on our own, he obviously felt he could trust me further when he disclosed his bitter criticism of Governor King's comments that he failed to adequately chart this area of N.S.W. when he was ordered to be the first ship to sail through Bass's strait to Sydney.

It seems he was appointed to sail the Lady Nelson, the brand new untested design of ship, to Port Jackson, and place the ship under the command of Lieutenant Matthew Flinders, so that Flinders could commence circumnavigating Australia Felix.

He, Captain Grant, was to be given command of the naval ship Supply at Port Jackson. When he arrived at Port Jackson, Flinders had already left for England to obtain a ship, and the Supply was a rotten old hulk that would never sail again.

While Governor King recognised his superb seamanship in getting the Lady Nelson to Port Jackson, he felt Grant should have spent a lot more time surveying the coastline on the way.

James felt that the Duke of Portland's information and orders, and Mr Banks' map, were not taken into account by the Governor.

The Duke of Portland's orders that Lt. Grant received at the Cape of Good Hope stated that the strait was in the vicinity of 38 degrees latitude, and the small map given to him by Mr Banks led him to believe that all he had to do was sail knowing his position relative to latitude 38 degrees south. In fact that is the latitude of the Cape he discovered and named Cape Northumberland, a first landfall in Australia.

The land after, apart from the other three capes, Cape Bridgewater, Cape Nelson, Cape Otway, kept falling away clockwise to the east but definitely southerly. This drove him further away from latitude 38 degrees. He tried several landings but they were unsuccessful. Very deep water prevented anchoring and unfavourable winds could have driven him onshore. Firewood and stores were getting low, the winds were now very unstable, so he felt that the safety of the ship and crew obliged him to shorten surveying and make his way to Sydney.

During our stay in Western Port we moved the Lady Nelson several times to assist in the surveying, obtaining water and firewood, and trying to reduce the physical effort in rowing, sailing. Once the ship nearly got stuck on the mud surrounding Elizabeth Island, but we got free by dropping anchors and winching off.

I nearly drowned twice! The first time, when the Lady Nelson was anchored at Churchill Island, and Captain Grant was overseeing land clearing so that a large variety of seeds could be planted, he sent Lieutenant Murray, myself, and some people to explore and chart the area around Seal Islands. After we had departed bad weather set in that prevented us landing. We eventually anchored off a sandy beach, which appeared to have no surf. We were suddenly surprised by a heavy swelling sea that rolled on the beach followed by another that filled the boat with water, and washed it up on the beach. No lives were lost, but we had to swim very strongly to reach the beach.

The second time, Captain Grant and myself spent two days and two nights exploring part of the northern arm. We ran short of drinking water but we heard a bull frog croaking and found a wet area with enough of a bog to fill our flasks. The weather turned wet during the second night, so we decided to return to the Lady Nelson. We set off at three a.m., to take advantage of the ebbing tide. But the tide was very fierce. We rushed into rough water, suddenly the boat started to spin wildly, shipping a lot of water. Next thing I recall was James gripping me by my belt, and dragging me back into the boat where I fell in a heap in the bottom full of water. I lay there getting dizzier and dizzier, when suddenly we were propelled out of the maelstrom. I started to vomit, but James recovered quickly. Eventually we climbed aboard the Lady Nelson.

With various people I have spent some time rowing and camping up Bass's River, obtaining water, fishing, and refilling water barrels. I have only gone as far as the fresh water. From there the trees and branches prevent further access, but it does look like the river meanders for several more miles up into the hills in the distance.

The area north of that good snapper fishing spot at Sandy Point on the western side, occupied me in exploring and surveying that arm for four days. At its absolute northern extremity the water bends away in a clockwise fashion to the east. At low tide numerous sand and mudflats appear. Not a good area to anchor a fleet. In the immediate area I found two deep channels that wind their way to the west. Keeping in mind Governor King's secret instructions, I also discovered a small creek just north of one of the channels, in a small bight.

After following the creek, I found it was possible to climb up the southern side of part of an escarpment. The view was splendid. I could see roughly 180 degrees of water-across to the large hill on the eastern side of the eastern entrance. Probably the entrance to Bass's River. Tortoise Head, that large peculiar hill that is narrowly separated from land by a narrow small spit, and Churchill Island. I'm not sure that a fleet would anchor in this area due to very strong tides, but the Governor and Colonel Paterson will be interested. I took some bearings, just in case guns would need to be mounted.

Francis Barrallier's map of Western Port, made with assistance from Murray. SLV.

Previous Chapter | Chapter Selection | Next Chapter | Download Chapter